Spills: Let There Be Light

What in the world are spills?

Spill Vase, 1830–70. Probably made in Bennington, Vermont. Parian porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. Charles W. Green, 1947, 47.90.16

Spill Vase, 1830–70. Probably made in Bennington, Vermont. Parian porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. Charles W. Green, 1947, 47.90.16

A British dictionary published in 1855 defined a spill as “A strip of paper rolled up to light a lamp or cigar.” The word loosely derives from “spile,” a small wooden peg. Although “spills” had been around for a long time, the term was not in use until the 19th century, when it first appeared in British dictionaries. Americans seem to have picked it up a little later, and in 1877 Webster’s defined a spill as: “A small roll of paper or slip of wood for lighting lamps, and the like.” For many years, people simply used expressions such as “pieces of paper,” a “paper match,” a paper “candle-lighter,” or a “neatly twisted paper cigar-lighter.” Wax tapers were also commonly used to light lamps and candles. “You should have some wax tapers on purpose to light your candles with, as paper makes a dirt, and flies about the room; besides it generally sticks to the candle and causes it to burn dim,” Robert Roberts recommended in his 1827 House Servant’s Directory. And in 1848, Chambers’s Information for the People pointed out: “It is always safest to light candles and lamps with a small wax taper, which can be at once blown out.”

Spills were usually placed in vases on the mantel to provide easy access to the fire from which they were lighted. In 1869, Catharine Beecher and her sister Harriet Beecher Stowe advised: “Lamps should be lighted with a strip of folded or rolled paper, of which a quantity should be kept on the mantelpiece.” Spill vases were made of glass, ceramic, and other materials and can sometimes be seen in paintings and drawings of the period, such as John Carlin’s painting Forbidden Fruit (1874).

Before the invention of matches, lighting fires was difficult. People had to use a tinder box, which contained a piece of flint, a steel striker, and tinder, such as charred rags. These items would produce a spark that could ignite a brimstone (sulfur)-coated “match” with which to transfer the flame. Vigilance was the order of the day if one wanted to keep the home fires burning. The safety match (which was made with red phosphorous) made life a lot easier, but it was not in common use until after 1860.

People made spills at home from writing paper, old newspapers, and even colored paper. In 1850, Eliza Leslie wrote: “They should be made of waste writing paper cut into long slips, and folded, and creased very hard. If of newspaper or any other that is not stiff enough, the flame will run along them so fast as to endanger your fingers.” Although Leslie advised against making spills out of newspaper, a story published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1876 described an impoverished woman using newspaper spills as a light source for nighttime reading because she had no candles.

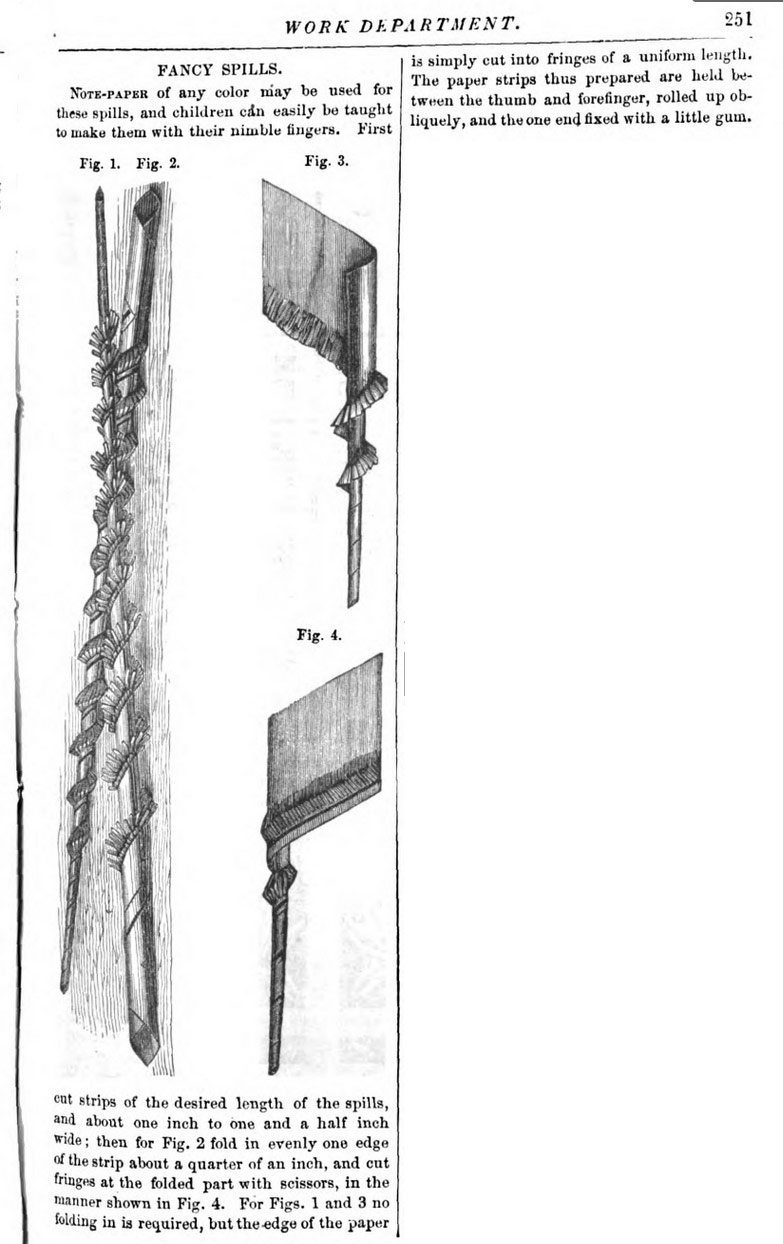

“Fancy Spills,” Godey’s Lady’s Book, September 1878

Fancy ornamental spills combined home décor with practicality. Nineteenth-century craft gurus provided instructions in magazines, just as Martha Stewart would do today. “To make ornamental spills, bright coloured papers, and also gold and silver paper are needed,” Cassell’s Household Guide directed in 1869. And Miss Matty Jenkyns, a character in Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1853 novel Cranford, excelled in making “candle-lighters, or ‘spills’ (as she preferred calling them), of coloured paper, cut so as to resemble feathers.”

People who like to curl up with a good 19th-century novel will find other scattered mentions of spills. Sometimes they are even used as clues in Victorian detective stories, such as in “The Blue Dragoon” (1855): “The police had not smoked, and, therefore, the thieves could be the only persons who had thrown the spill on this spot.” And there’s this riveting passage from After Dark (1856), a collection of short stories by Wilkie Collins, the master of the sensation novel:

“Give me two minutes,” says I, “and don’t let anybody come near the door—whatever you do, don’t let anybody startle me again by coming near the door.”

I took a little pull at the thread, and heard something rustle. I took a longer pull, and out came a piece of paper, rolled up tight like those candle-lighters that ladies make. I unrolled it—and, by George! there was the letter!

Illustration by Hugh Thomson from an 1892 edition of Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell. Spill vases flank the mantelpiece.

Spills are now largely forgotten, but their history can inspire us as we light our candles today: “I love candles. A wax candle is one of the prettiest and most graceful things imaginable. . . . How reliable it is; the instant it is held to the spill it lighteth cheerfully, and when its services are no longer required, how . . . amiably it allows itself to be put out” (The Welcome Guest, 1860).

Margaret Highland, Historian

Mansion Musings, USA

PROFILE

Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum is home to one of the most beautifully situated historic houses in the city of New York.

Musings on the preservation, restoration, and interpretation of this historic house and its gardens.

Main Research Source

- Spills: Let There Be Light by Margaret Highland(04/12/2017)

I updated the ‘Fancy Spills’ image to include the instructions. Source: Hathi Trust