Technological Disobedience: Ernesto Oroza

Illustrations by Alice Oehr for Assemble Papers

In August 1990, the Cuban government, led by Fidel Castro, announced a new Special Period in Time of Peace – a euphemism for the economic crisis in the country, resulting from its disintegrating commercial and productive links with Eastern Europe as it sought autonomy from the Soviet Union. This ‘special period’, the effects of which deepened in the decade that followed, acted as a summons to the Cuban people to struggle and sacrifice in the hope of a better future. It established a framework of austere rationing, where many individuals were forced into a lifestyle of unrelenting scarcity, challenged to live without many products that might otherwise grant a ‘modern’ lifestyle.

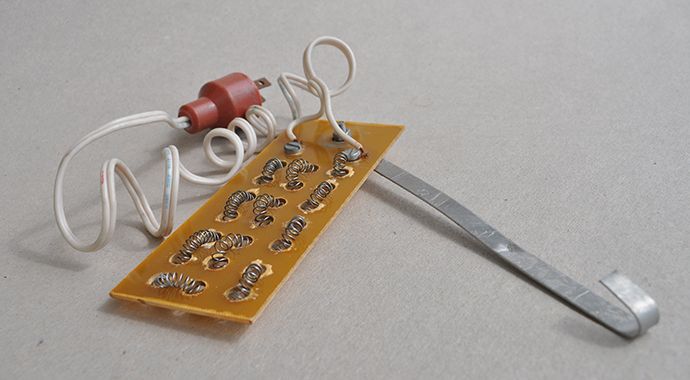

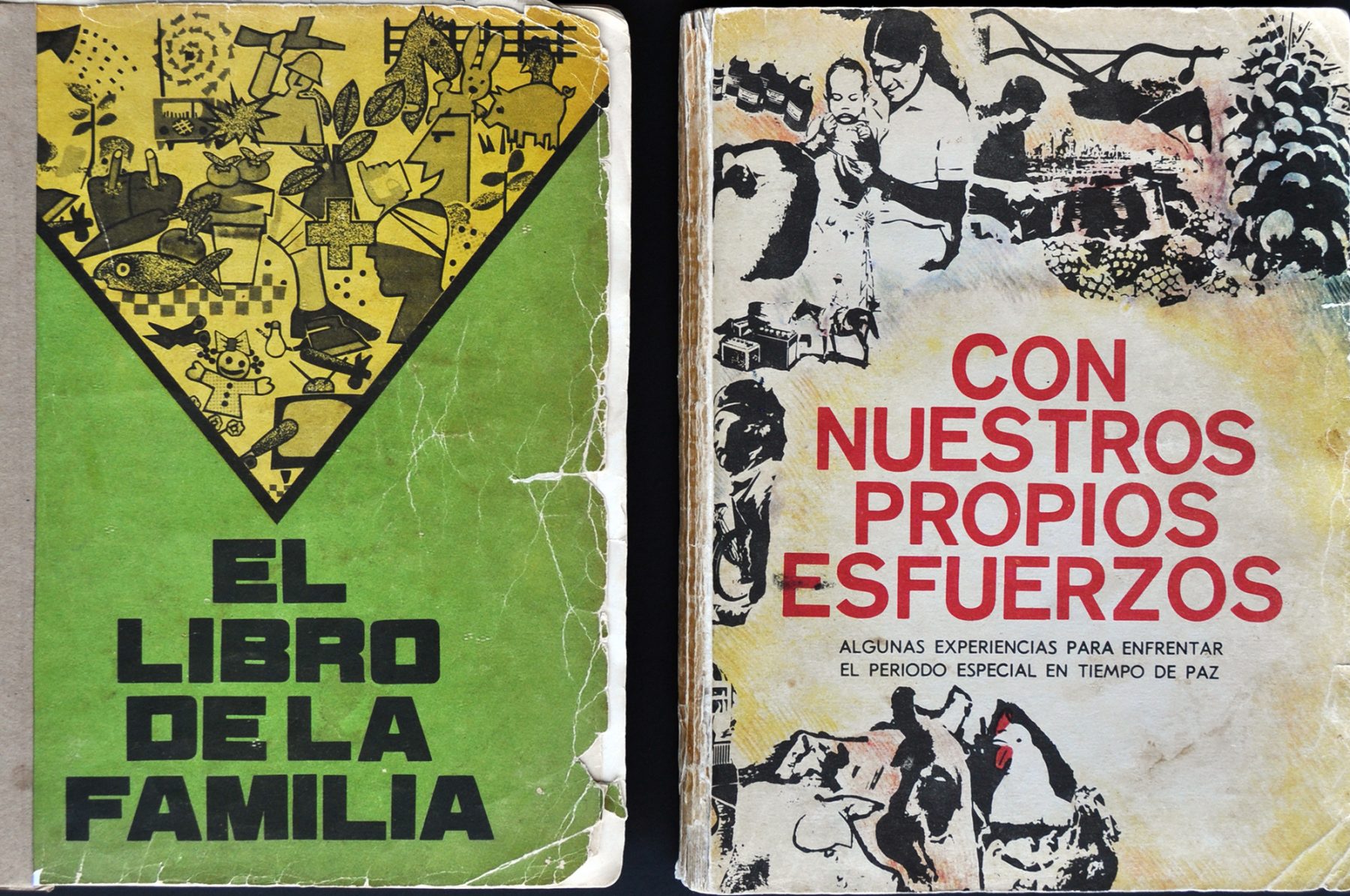

A fundamental shift in how civilians perceived objects and their material culture began to emerge. Commodities were pulled apart and resurrected into new and useful forms: aluminium dinner trays were hoisted onto poles to repair broken aerials, discarded soft-drink cans became vessels for kerosene lamps and vinyl records were cut and thermoformed as replacement blades for missing fan heads. These individual hallmarks of creativity did not exist in isolated practice – instead, they were passed on through word of mouth, spurring entirely new production and consumption models based on community and discourse, in contrast with the authoritative embodied designs of the West. This independent production was documented by the Cuban government and published under the title Con Nuestros Propios Esfuerzos (With Our Own Efforts) to encourage and empower the population to keep building, repairing and reinventing their surroundings.

Ernesto Oroza is a Cuban designer (now based in Aventura, Florida) who spent most of his life in Havana, where he experienced this phenomenon firsthand. Through his Technological Disobedience project, Oroza has archived hundreds of objects of invention that systematically resist mainstream protocols. Together, these objects highlight ingenuity as well as the sociopolitical and economic forces that inform design.

Elliott Mackie: What first inspired you to begin collecting and documenting these artefacts of Cuban ingenuity and resourcefulness?

Ernesto Oroza: When I graduated from design school the country was entering the economic crisis. I dedicated most of my time to developing a personal project – I wanted to articulate my own way of doing design, influenced by Italian radicals like Andrea Branzi and Ettore Sottsass. I would spend my days drawing furniture and objects I believed to be experimental and radical. At the same time, my mother-in-law would repair the fan and other objects in our house that were rapidly deteriorating. She invented meals using barely any ingredients, raised a pig on our balcony and created a machine to make cigars because the cost of them on the black market was astronomical. One day I realised that, in fact, it was my mother-in-law who was doing radical design. I decided to pay attention and learn.

EM: Many of the inventions you reference in your work were born out of fundamental needs that were not catered to during the embargo. Can you recount any personal stories of your own inventiveness during this time?

EO: I want to clarify that, in my experience, it was not only the result of the American embargo on Cuba that these fundamental needs were not met. We Cubans see it as an ‘internal embargo’ – the restrictions of economic freedoms of individuals and corruption, and the squandering and systematic inefficiency of the political system on the island.

I think my practice, in the first few years of the crisis, was ‘schizophrenic’. I tried to make experimental designs that were disconnected from reality, and, on the other hand would spend much of my day creating solutions to meet the needs of my family. I soon learned that these tasks that I was developing in the house, which responded directly to the demands of the home, could be interpreted through the culture and history of design. The majority of my ‘objects of necessity’, as I later decided to call them, disappeared in the whirlwind of my family’s survival and I never had the chance to chronicle them.

In 1993 I made a bench for family reunions. My eldest son had just been born, and I built the bench on the roof of the house where we had a fantastic view of Havana. The bench was made from a large plank and the frames of two school chairs placed at each end. In 2001, I decided to exhibit it. This bench illustrates the evolution in my thinking: When I didn’t understand my personal situation, I wanted to create unique objects that hadn’t been thought up by anyone else. Later, I understood this makeshift, improvised bench – like many other objects I made – was the result of embracing collective design. Ideas were passed on from one person to another in the city. Havana was full of makeshift benches and other objects of necessity made from the same materials, adopting the same principles of construction as those we were making at my house. I was liberated from the ‘innovation’ per se that we are indoctrinated with at design school and that, in my opinion, neglects the social problems and the importance of context. I started to notice through small, humble gestures how to collect, repair and reuse, and the potential to alter and question means of production. I understood the political dimension of these gestures and the unorthodox, inclusive and liberating character of what, years later, I would come to call ‘technological disobedience’.

EM: In the 1970s Charles Jencks forged a new architecture and design era through his Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation, which for many was a manifesto for utilising everyday materials in design. There are clear parallels between Jencks’s Adhocism and the Cuban military-issued text With Our Own Efforts, although Cuban ‘technological disobedience’ appears across many fields, not just architecture and design. How was communication between disparate fields encouraged during this period in Cuba?

EO: Despite the abundance of inventions across all sectors of society, it didn’t mean they were welcomed everywhere and by everyone. It’s true that this inventive vernacular reached every corner of life in the country, but the expansion of the phenomenon was due to other factors. […] Some of the concepts and terms I developed were in response to the need to elaborate arguments for discussions with professionals and reject the derogatory titles I frequently heard in relation to this type of production – I tried to bring the dialogue back to the core values of the objects regardless of their appearance. ‘Kitsch’ and ‘povera’ design were just some of the labels I saw placed on these objects and in the readings I did about them. In all areas (art, architecture, design, sociology, anthropology) this form of production and its study seemed intrusive, provocative and askew.

At the start of the revolution, repair and reuse were encouraged, and almost seen as a duty to the Communist Party, but during the 1990s the government criminalised this type of production. (Fidel Castro named these objects “energy-devouring monsters” in a video you can find on YouTube.) On a couple of occasions, the editors of two local magazines asked me to remove words like ‘precarious’ and ‘poverty’ from my texts. Still today, for many, this is a type of production that shouldn’t be shown or given any attention.

Contrary to this, The Book for the Family and With Our Own Efforts were both edited by the Armed Forces and the Federation of Cuban Women, and even though they were circulated in a very restricted sector (the army), they responded to a particular desire to involve the people and were more affiliated to the less dogmatic spirit of the ’60s.

EM: Both ‘technological disobedience’ and ‘adhocism’ encourage the revaluing of discarded material, and yet neither are anti-design – they both embody design thinking, and though similar in the upcycling of materials there seems to be a divergence within the objects from Cuba.

EO: I agree. [Cuban] production was informed by necessity and by urgency – there was no interest in recycling, and the ecological benefits of using discarded materials and objects were not considered. In fact, many of the productive processes which took place in homes, like plastic injection and smelting aluminium, were polluting and unhealthy, and the improvised workshops didn’t have adequate means to eliminate the toxic vapours or treat the waste from the production.

EM: Do you think the West can learn from Cuban ‘technological disobedience’, or is this a dangerous idea, given the desperate conditions from which it eventuated?

EO: Poverty is not a choice, but an individual who is aware of their needs and finds ways to meet them is very inspirational. It is a versatile and important resource and is important in any context. In my work, I try to establish these connections, articulate the political dimensions of this practice and connect these ideas with other creative movements.

I don’t know if one can learn specifically from the Cuban case because of the peculiar conditions in which it was developed, but I do think it’s a phenomenon that has parallels in other countries and productive contexts that one can learn from. ‘Maker’ culture is something frequently mentioned as a parallel phenomenon to that in Cuba, but I think it is actually a ‘hacker movement’ and its techno-political positioning a creative movement that Cubans could learn from.

EM: I have read that the Soviet washing machine played a crucial role in Cuba’s capacity to develop new objects. What do you think have been the benefits of standardisation and industrialisation with regard to the communication of models of design within Cuba?

EO: I have been writing about this topic recently. It is common to stigmatise the standardisation and norms as a negative aspect of globalisation. In cultural and post-colonial discourses, standardisation is presented as a global force that kills local culture.

What happened in Cuba, and perhaps in other contexts, proves that standardised and normalised objects and materials in situations of urgency become a means to energise the expansion and propagation of ideas. First of all, because of the common knowledge that is constructed socially around normalised objects and materials. Secondly, because of the sheer volume – an intrinsic intrusion of many standardised productions – of standardised and normalised objects that makes them an accessible resource. For example, reparation, via a standard route, became an institution on the island. A maker of spare parts for fans in the province of Holguín, through another standardised object such as a vinyl LP, introduced into the market blades made by cutting and thermoforming the disc.

In the case of the Soviet Aurika 70 washing machine, it came with a washing machine and a drying machine. Given the climate on the island, the mechanical drying could be done away with. Many individuals used the motor from the dryer for other purposes. This was the real motor of the revolution: there was no sector of life in which this object was not being reused in some way. I have records of its presence in dozens of artefacts including lawn mowers, key-cutters, vegetable cutters and fans.

EM: When you look at the objects that you’ve collected over the past two decades, how do you see them? When assembled into an exhibition, for example, what are you saying about Cuba’s so-called Special Period?

EO: I don’t see it as a collection, though at times I have misused the term and have been translated incorrectly. I understand these sets of objects as a library, an archive, or a materioteca (material library).

I think these objects can be interpreted in various ways. For me, they operate as a catalogue of collective creativity and the many other forces that shaped Cuba during the Special Period. As a whole they can be articulated as an example of cultural resistance. Because of their provisional character they can be interpreted as utopian objects, full of hope. I think there is an ideology in them, a unique relationship to beauty, comfort and technique.

My relationship to this production is experiential – I grew up with the crisis. At the same time I tried to create a critical distance and understand the political dimension of these tactics. Today, I can draw parallels between these practices and those developed by Cubans and Haitians in Miami or in other contexts. I’m interested in these recurrences, patterns and individuals who find similar solutions in different places, seemingly under different economic and ideological forces. These recurrences point to economic and political models that are increasingly more perpetual and homogenous. In this sense, I feel like these objects from the Special Period are becoming gradually less special. On one hand, this is bad because it means that the crisis is expanding. On the other, it’s good because we’re forced to confront it with imagination everywhere.

This article originally appeared in Issue 7 of Assemble Papers, ‘In/formation‘. Credit to Gabriela Holland, who translated Ernesto’s answers from Spanish. To read more about Ernesto’s work, visit ernestooroza.com. Find out more about Elliott Mackie’s work at elliottmackie.com.

Technological Disobedience, Cuba

was used when creating this post

PROFILE

Ernesto Oroza has been collecting examples of DIY inventions from Cuba since the 1990’s. The Soviet Union collapsed (1991) marking the end of the USSR’s aids to the small island. The Cuban government proclaimed a “Special Period” of extreme rationing and shortages. A new era of creative enterprise started dedicated to making and tinkering.

It’s a true story of people using their own creativity and ability to improvise, invent, repurpose and repair objects.

Technological Disobedience is a research blog / virtual archive for the virtual exhibition « Futurs non-conforme », in 2016.

The term “technological disobedience” was first published in Oroza’s RIKIMBILI book. Une etude sur la désobéissance technologique et quelques forms de reinvention. [A study on technological disobedience and some forms of reinvention.]