A Review on Upcycling: Current Body of Literature, Knowledge Gaps and a Way Forward

Abstract—Upcycling is a process in which used materials are converted into something of higher value and/or quality in their second life. It has been increasingly recognised as one promising means to reduce material and energy use, and to engender sustainable production and consumption. For this reason and other foreseeable benefits, the concept of upcycling has received more attention from numerous researchers and business practitioners in recent years. This has been seen in the growing number of publications on this topic since the 1990s. However, the overall volume of literature dealing with upcycling is still low and no major review has been presented. Therefore, in order to further establish this field, this paper analyses and summarises the current body of literature on upcycling, focusing on different definitions, trends in practices, benefits, drawbacks and barriers in a number of subject areas, and gives suggestions for future research by illuminating knowledge gaps in the area of upcycling.

Keywords—circular economy, cradle to cradle, sustainable production and consumption, upcycling, waste management

I. INTRODUCTION

UPCYCLING is often considered as a process in which waste materials are converted into something of higher value and/or quality in their second life. It has been increasingly recognised as a promising means to reduce material and energy use. For example, Braungart and McDonough [1] pioneers of industrial upcycling (i.e. Cradle to Cradle), have advocated radical innovations for perpetually circular material reutilisation as opposed to current recycling practice, and helped a number of companies to incorporate upcycling in their businesses (e.g., Steelcase, Herman Miller, Ford). Szaky [2] sees object upcycling as one of the most sustainable circular solutions since upcycling typically requires little energy input and can eliminate the need for a new product from virgin materials. Such object level upcycling has been actively promoted and practiced by increasing number of entrepreneurs including TerraCycle, FREITAG, Reclaimed, The Upcycling Trading Company and Hipcycle to name a few.

The growing number of publications on upcycling in various subject areas also shows that the concept of upcycling has received more attention from numerous business practitioners, researchers, and craft professionals and hobbyists in recent years. According to the Google Books search done by the author in September, 2014, upcycling related books have been published since 1999.

II. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

III. RESULTS

A. Descriptive Analysis: Trends in Upcycling Publication

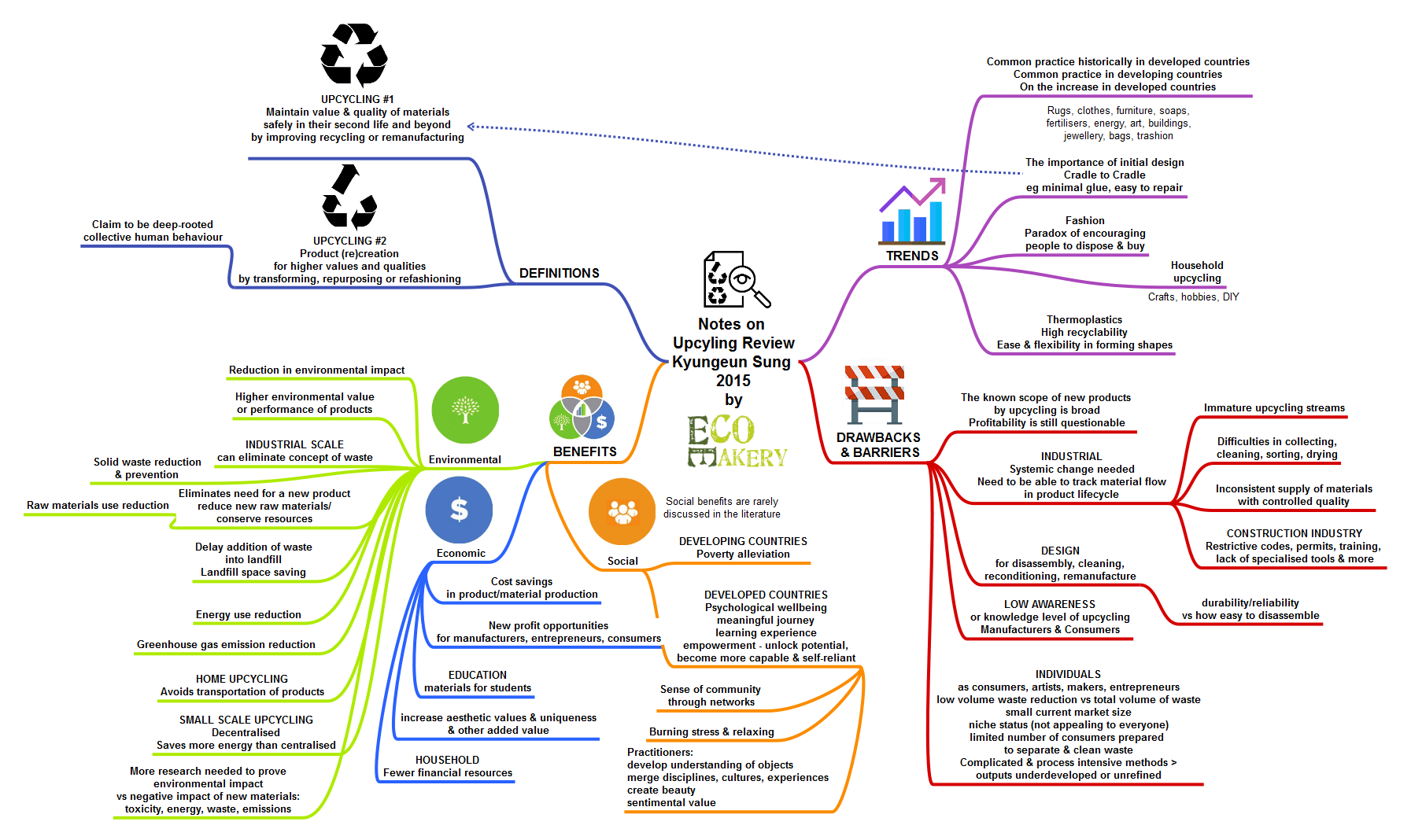

B. Definitions of Upcycling

- Nine Definitions originated from Braungart and/or McDonough

- Three definitions originated from Pilz

C. Trends in Upcycling Practices

Even though the term, upcycling, is a neologism, Szaky [2] suggests that it has existed for thousands of years as an individual practice of converting waste or used objects into higher value/quality objects. Szaky explains that reuse and upcycling were common practices around the world before the Industrial Revolution and are now more common in developing countries due to limited resources. Recently, however, developed countries have paid more attention to object/product upcycling in commercial perspectives [2], [43], [44] due to the current marketability and the lowered cost of reused materials [17]. In the United States, for example, the number of commercial products by product upcycling increased by more than 400% in 2011 [44]. The scope of products produced by upcycling varies: rugs from fabric scraps, refashioned clothes, remade furniture, soaps and fertilisers (and energy) from organic waste, artistic objects from scrap metal, and even a whole building from reused components from deconstruction among many others [8], [9], [15], [17], [26], [27], [45]. The creation of jewellery, bags, clothes, and other fashion items by upcycling, in particular, is also called ‘trashion’ [8], [26]. Competitions have been organised around trashion; numerous websites are promoting and selling commercially upcycled products; and a number of digital and printed resources explaining how to upcycle at home are available [13].

Braungart and McDonough [1], [5], [49] stress the importance of initial design which takes into account future upcycling. For example, a minimal amount of glue in assembly is recommended for quick and easy disassembly for safe and easy repair, reconfiguration, return, reuse or recycling. The Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute [50], therefore, administers the Cradle to Cradle CertifiedTM Product Standard which guides designers and manufacturers through a continual improvement process for products in terms of material health, material reutilisation, renewable energy and carbon management, water stewardship, and social fairness. Braungart [10] also adds the dimension of leasing and take-back systems for more effective reutilisation of materials by manufacturers. A number of the world’s largest companies have made some of their products Cradle-to-Cradle certified, and integrated upcycling in their businesses, such as Steelcase, Herman Miller, Berkshire Hathaway’s Shaw Industries, Ford, Cherokee, and China’s Goodbaby [5].

D.Benefits

Many authors generally agree that upcycling provides reductions in environmental impact [13], [23], [47], [51] or contributes to a higher environmental value or performance of products [15], [25], [33], [52]. Braungart and McDonough [1] says industrial upcycling alters linear progression ‘from cradle to grave’ by material reutilisation in safe, perpetual cycles, which therefore eliminates the concept of waste and reduces toxic materials in biosphere. Similarly, some authors pay more attention to the role of upcycling in solid waste reduction [23], [25], [26], [32] or at least in delaying the addition of waste to landfill [8] or saving landfill space [51]. Product (re)creation by upcycling also eliminates the need for a new product [2], therefore reducing new raw materials use and conserving the natural resources [25], [33] as well as reducing energy usage [33], which leads to greenhouse gas emissions reduction [15]. Comparatively, upcycling uses less energy than recycling [2], [25], [53]. When upcycling is done at home, it can be even more environmentally friendly than industrialised upcycling, in avoiding any transportation of the products [2]. Likewise, upcycling as upgraded recycling on a small scale and decentralised processes (e.g. using RecycleBot 5 technology) could save more embodied energy than if it were centralised [34].

Along with environmental benefits, general economic benefits are also commonly stated by many authors. Some view economic benefits largely in cost savings in new product production [32], [39], [54] or in new stock material production [36], [55]. In art, craft and design education, upcycling is also an easy and economical way of getting materials for student projects [27]. The economic benefit is not limited to cost savings but also includes new profit opportunities by increasing the aesthetic values of existing products [25], giving uniqueness to the design [56], improving material quality or value (e.g. reinforcement, adding aroma, etc. to polymers) [37], [54], [55], and providing other added values to materials or products [15], [32], [47], [57]. The uniqueness of upcycled products in textiles and fashion items is one of the most important purchasing criteria for mainstream customers [56], hence upcycled products in those markets often carry the names of high street brands [8]. Acknowledging this, product upcycling has gradually come to be recognised as a viable business opportunity [13], [56]. Big corporations can also upcycle facades in their building for rebranding companies [52]. Apart from the industrial (or institutional) level, household upcycling can also be economically beneficial for consumers by fulfilling needs with fewer financial resources and having a potential niche market opportunity [6], [58], [59].

Social benefits are rarely discussed in the literature, although Bramston and Maycroft [26] suggest that upcycling practitioners gain an opportunity to develop inherent understanding of objects, merge disciplines, cultures and experiences, and create subjective and individual beauty while keeping the sentimental value of a used product. Szaky [2] explains how object upcycling has been used to help alleviate poverty in developing countries. Other possible social benefits related to human psychological wellbeing were summarised by Sung and colleagues [59] as experience benefits (the upcycling process as a meaningful journey and learning experiences), empowerment benefits (unlocking potential, and becoming more capable and self-reliant), a sense of a community through upcycling networks if any, and burning stress and relaxing, primarily citing Frank [6], Lang [58] and Gauntlett [60].

5 An open source hardware tool for distributed recycling, able to convert post-consumer plastic waste to polymer filament for 3D printing [34].

E. Drawbacks and Barriers

For industrial upcycling, both as upgraded recycling and as remanufacturing, some authors assert that a systemic approach (i.e. whole supply chain change, recycling networks, multidisciplinary approach) is required [5], [28], [32] to make upcycling truly work. Companies need to have a system which tracks the material flow during the lifecycle of each product they produce, and plans for how to take back and reutilise them for another product [5]. This system necessarily entails the design for easy disassembly, cleaning, reconditioning and reassembling for remanufacturing [28]. Such a systemic approach is not easy to achieve due to a number of issues as follows. Technical issues include (1) possible trade-offs between current value and quality of the materials or products and future upcyclability (e.g. durability/reliability vs. how easy to disassemble) [52]; (2) immature upcycling streams of different technological capacity with inability to handle all types of materials [20]; (3) difficulties and inefficiencies in collecting, cleaning, sorting, drying, and homogenising [37], [52], [61]; and (4) inconsistent supply of materials with controlled quality (in terms of composition and impurities) and process complexity [32]. These issues may be likely to discourage big companies to make a systemic change. For instance, Chanin, an eco-friendly fashion company owner, states that upcycling in the textile industry works well on small and focused projects on a local basis but remains impractical on a large scale [61].

Other issues appear to be mostly related to low awareness or knowledge level of upcycling. McDonough and Braungart [5] claims that companies have fear that the changes are either impossible or too costly, or that they do not have enough information for a change. Misunderstanding and misinterpretation of the terms and concepts related to upcycling might also lead to unintended negative environmental consequences [5].6 Eder-Hansen and his colleagues [20] mentions that consumers’ lack of awareness of an option for their products’ end of life could be another serious barrier.

Munroe and Hatamiya [36] listed systemic issues slowing the adoption of upcycling specifically in construction industry. The issues include restrictive codes and standards, lack of trained deconstruction workers, lack of specialised tools, need for new architectural design and construction practices, lack of economic disincentives for dumping, need for permitting incentives and risks in the deconstruction process.

For individuals as consumers, artists, makers, or entrepreneurs, there are different issues which might make upcycling less attractive. Szaky [2] gives some examples of potential problems: (1) relatively low-volume solution for waste reduction/prevention compared with the total volume of waste; (2) small current market size; (3) the niche status of upcycled products (i.e. not appealing to everyone); and (4) the limited number of consumers who are willing to separate and clean waste (e.g. packaging) for upcycling purposes. Bramston and Maycroft [26] adds that individuals also find access difficult to many complicated and process-intensive production methods, and that the outputs from consumers can therefore often be underdeveloped or unrefined.

6 For example, misinterpretation of closed loops could lead to the conclusion that it is okay to design an toxic product in the first place as long as it could be reconfigured into another toxic product [5].

IV. SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

A. Descriptive Analysis

The cumulative frequency of the sampled publications demonstrated a recent surge of publication on upcycling since 2008. Two major approaches adopted – conceptual and case studies – also validated that the area of upcycling is relatively new and unexplored because, in general, when there is little previous knowledge, conceptual papers tend to appear more frequently [62], and case studies are considered to be an appropriate choice for study [63], [64]. The subject areas implied that upcycling has been understood mainly in the context of engineering, technology, design and business.

The industrial (sub)/sector distribution presented more research interest in fashion & textiles and plastic recycling. Fashion, in particular, is all about change, encouraging consumers to dispose of old products and buy more new [65], and thus, paradoxically has more market potential through upcycling. Taking into account that nature of fashion coupled with mainstream customers’ purchasing criteria (e.g. seeking uniqueness) [56], it is not surprising that academics and practitioners in fashion and textiles have published more literature on upcycling. The sampled publications also showed a strong focus on thermoplastics recycling probably due to the following reasons: (1) recent increase in the volume of the general plastic waste as a modern phenomenon and its negative environmental impacts [23], [51]; (2) high recyclability unlike thermosets [66]; and (3) the ease of processability and the flexibility in forming or shaping after recycling [17]. Besides fashion & textiles and plastic recycling, academic publications have not paid sufficient attention to, for instance, housewares, furniture, jewellery and accessories even though a lot of individual upcycling practices appear to be taking place in households to create these products as shown on numerous internet websites and blogs. The trend in practical upcycling books publications (53% of the sampled books categorised as ‘craft and hobbies’ and 10% as ‘house & home DIY’) also reflect such contemporary household practices. Future study on individual upcycling should therefore pay more attention to these product categories.

The literature distribution by country displayed the major role of the USA and several European countries in publication. This could be due to socio-cultural factors such as excessive consumerism and high volume of waste, and therefore more concerns about and interest in environmental issues than mere production efficiency and profitability in these affluent Western countries.

B. Synthesis: Upcycling Definitions, Trends in Practice,

Benefits, Drawbacks and Barriers

Despite variations among definitions, there were two dominant viewpoints in the sampled publications. One is based on material recovery of which the major aim is to maintain value and quality of materials safely in their second life and beyond by the improved recycling or remanufacturing. The other focuses on product (re)creation for higher values and qualities by transforming, repurposing or refashioning waste or used materials/products either by companies or by individuals. Would it be better to clarify such differences by saying, for example, ‘industrial upcycling based on recycling’, ‘industrial upcycling based on remanufacturing’, ‘individual upcycling based on product re-creation’, etc.? Such clarification may help avoid any confusion or misinterpretation. Similarly, the broad range of words used to define upcycling obscures the clear picture. How is upcycling fundamentally different from or similar to reuse, recycle, repurpose, remanufacture, refashion, resurface, transformation, etc.? Is it a trendy term to say improved or better reuse, recycle, or remanufacture? Or do all those words simply represent ‘how’ to achieve upcycling? An investigation into the clearer relationship between upcycling and more traditional ways of resource reutilisation may help to clarify where upcycling really stands. Value and quality, despite the common use in almost every definition, may sound ambiguous for many especially when used in the context of product (re)creation. It is because value can be assessed differently by individuals, and one of the important quality dimensions of certain products may include newness. Consequently, whether or not a certain activity or process satisfies the definition of upcycling would probably depend on product categories and how buyers or consumers perceive the value and quality of the outputs created by upcycling.

Practices in material recovery appeared to emphasise the importance of initial design and process innovation in companies for high upcyclability and safety. Yet industrial practices – who is doing what, when, where and how, and how (un)/successful it is – remained largely unknown. Practices in product (re)creation with used materials at the individual level were claimed to be deep-rooted collective human behaviours; yet how they have evolved over time, and how they can be harnessed at the household level to make bigger impacts has not been investigated. The commercial perspective of product (re)creation is recently acknowledged and the known scope of new products by upcycling is broad. Market potential (or profitability) of most of these product categories, however, is still questionable. Trashion, upcycling in fashion, seemed to be one of the successful examples, but scalability has not yet been proved. Considering the infancy of the upcycling-based market, feasibility and marketability studies focusing on specific industry and product category would be required.

The benefits of upcycling were discussed on the basis of the three pillars of sustainability – economic, environmental and social sustainability. Most publications referred to environmental and/or economic benefits but far fewer discussed social benefits. Environmental benefits included solid waste reduction (and prevention), landfill space saving, raw materials use reduction, energy use reduction, and greenhouse gas emission reduction. Economic benefits included cost savings and new profit opportunities for manufacturers, entrepreneurs and consumers. Social benefits in developing countries are mostly poverty alleviation and, in developed countries are more relevant to psychological well-being and socio-cultural benefits based on individual upcycling. These benefits, however, are mostly generic and descriptive rather than specific and quantified unless the papers deal with technical aspects of the upcycling process. More empirical research is needed to show how significant the environmental impact is through upcycling. When adding up negative environmental impacts from new materials, toxicity, energy, waste and emissions possibly involved in the process of upcycling (from collection of the used materials to (re)production and (re)distribution) to positive environmental impacts in a quantifiable way, is it still far better than any other ways of waste treatment for every product in every industry? Cost-benefit analysis with real-life cases (of design change, process innovation, new ventures, etc.) would be able to further confirm or dispute the cost-saving and profit generation potential. Social benefits are especially underexplored and it is hard to quantify the real impact. More structured longitudinal studies to monitor the social impacts in groups of people might help shed light on this relatively unknown area.

Drawbacks and barriers of upcycling were identified as many and varied, depending on the level of the upcycling (industrial vs. individual), types of industry, and contextual situations (e.g. market dynamics, regulations and policies, socio-cultural background, etc.). In order to ensure the success of upcycling – in terms of environmental, economic and social impacts – more case studies (industry- and product/material-specific) are required to list systemic issues to tackle.

C. Reflections on Research Methodology

V. CONCLUSION

APPENDICES

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

REFERENCES

Dr Kyungeun Sung

PROFILE

Design Researcher and Teacher focusing on Upcycling and Sustainability

I am Senior Lecturer in the School of Art, Design and Architecture at De Montfort University in the UK. My research is broadly concerned with design and sustainability, with a focus on upcycling, circular economy and net zero. I have research interests and expertise in sustainable design, craft, production, business, supply chains, behaviour, consumption and lifestyles. My research uses design as a tool for new product development, service innovation, behaviour change, scaling up niche sustainable practices/behaviours, and transitioning to the circular economy and net zero. I have published over thirty peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings and book chapters in my field with high-impact journals and high-quality publishers.

Main Research Source

I wondered what I could do with this information that could be useful for myself and others, so I put what I considered to be the main points in a visual format. If you find it useful, please let me know because that would encourage me to do more! Click to view: