What is Sashiko?

Sashiko is a very old form of hand sewing using a simple running stitch sewn in repeating or interlocking patterns through one or more layers of fabric. Originally designed for quilting together several layers of fabric for warmth and durability or for strengthening a single layer of fabric, sashiko patterns readily lend themselves to contemporary designs and projects.

Many Asian cultures have utilized sashiko stitching as a sewing technique since ancient times; however, sashiko is most commonly associated with the Chinese and Japanese. In ancient days, clothing was made from homespun fabrics woven from native fibrous plants such as wisteria and hemp and necessity demanded that this clothing be recycled for as long as possible. Unfortunately, these homespun fabrics gave little protection against the bad weather or cold. Along the way, some creative sewer discovered that garments became much warmer and functional if a lining was stitched in or if several layers of fabric were stitched together.

The first milled cottons introduced were very expensive to buy and so new methods were developed to extend the life of the fabric. Long cotton threads were often stitched through the entire bolt of woven cloth at regular intervals to add strength to the fabric. And by layering this fabric and then adding sashiko stitching to hold the layers together, clothing could be produced that provided much better protection from the elements and that lasted longer. Even today certain items such as tabi (the socks worn with sandals) are still made with fabric produced by this method.

Later, as cotton became more plentiful and less costly to buy, it was used in other non-traditional ways such as underwear and bed coverings. It was then that sewers also began using sashiko for decoration as well as practicality. Traditional Japanese patterns and motifs became incorporated into sashiko stitching and much more intricate designs developed. Today, sashiko is used primarily as decoration on items such as curtains, table cloths, clothing and accessories.

Designs

——-

As with many other art forms, most patterns are actually simplified representations of things found in nature and are often modeled after plants, birds, animals, natural phenomena such as clouds, tools, implements of war, or written characters from the language. A distinctive element in all sashiko patterns is the use of space–Japanese designs especially make full use of blank or “negative” space as an integral part of the overall pattern.

Examples of designs primarily drawn from nature include:

CLOUD (“kumo”) – clouds were thought to be vehicles for Buddha and other celestial beings and was the symbol of rulers and authority;

HEMP/FLAX LEAF (“asa-no-ha”) – a motif often used in Buddhist sculpture and scrollwork to represent radiating light or the inner light of the soul;

BAMBOO (“chiku”) – symbol of vitality and prosperity;

TORTOISE SHELL (“kikko”)- symbol of good fortune and eternal youth.

Often just an outline of a shape is used to represent a much more complex image such as symbols of seasonal change. And even the simplest sashiko patterns may have beautiful names symbolic of the natural image that comes to mind. Rising Steam (tatewaku) or Seven Treasures of Buddha (shippo) are examples of this type of naming. Some historians even believe that an abstract version of a chrysanthemum blossom may have served as the model for the common Dresden Plate pattern.

Single designs with specific symbolic meanings are called Mon (crests). The well-known family crests (kamon) are actually very abstract representations of ancient textile designs. In the early days the aristocracy used motifs extracted from textiles as a type of personal and family identification. These designs were then painted onto their possessions and stitched on clothing.

Fabric

——

Any number of layers that can be comfortably worked may be used, or just a single layer of fabric may be used for embroidery work. Two layers of fabric sandwiched with a layer of batting can be used for quilting.

In Japan, sashiko is most commonly seen on indigo-dyed cotton fabric with colors ranging from a pale light-blue to the deep blue-black usually associated with sashiko. However, other materials such as silk or wool, and even other colors and prints are becoming much more popular. Keep in mind that it is the beauty of the stitching that is important in sashiko, so the fabric pattern or colour should be kept subtle for best results.

Evenweave fabrics that are tightly woven are excellent for use with those sashiko patterns that are stitched in straight lines. If doing handwork, it becomes a simple matter to just count the threads as you stitchThis creates a pattern that crosses at regular intervals (such as every 4 threads for instance).

Always prewash and iron your fabric. Natural dyes, such as indigo, may bleed with washing. Extra care in setting the color should be taken. Iron your fabric from the wrong side. Some natural-dyed fabrics (especially indigo) tends to “shine” if ironed with too high of a heat setting. With this type of fabric, always use your iron’s Cotton (or cooler) setting. Many people even iron their fabric to straighten the weave so it won’t shrink during washing.

Thread

——

Traditional sashiko thread is 100% cotton and has a “heavier” look than quilting thread. Sashiko thread can be purchased through most quilting stores or specialty dealers. On cotton fabric, other good choices include crochet thread, Perle cotton (#5 is a good weight), or four strands of embroidery floss.

Different fabric weights may require other threads: silk embroidery floss, other weights of Perle cotton, blending filaments (including metallics) can all be used.

When doing sashiko by machine, other suggestions for threads include buttonhole twist for the top thread. If you want to use a thinner thread such as a metallic or silky type, use the thread doubled on top. However, note that many machines do not handle this type of thread well or at all, so check your manual for instructions first.

If hand stitching, cut your threads 18-20″ in length to avoid tangling and knotting while stitching.

Tracing the Design

——————

Trace your design onto the RIGHT side of a fabric piece that is approximately 2-3″ larger than the actual size needed. This will allow for any of the fabric being “eaten up” by the stitching, as well as extra room needed to adjust the pattern.

Patterns can be transferred on a light table (or by using some other type of back lighting) or with dressmaker’s carbon, French chalk or a quilter’s marking pencil. AVOID USING A MARKING PEN since sashiko thread can be very sensitive to the chemicals and might pick up the colouration. Consider using different colours of marks to represent the stitching order if possible. YOUR DESIGN NEEDS TO BE AS ACCURATE AS POSSIBLE. Since sashiko stitching uses a very even stitch length, any errors in the design transfer will show up noticeably in the finished work.

Templates for common designs, similar to those used in quilting, are available commercially as well. You can also make your own patterns out of a heavy weight cardboard or template plastic.

The Stitch

———-

The beauty of sashiko is in the stitching design itself which is a simple running stitch done traditionally done without a hoop. The stitch count is usually 5 to 8 per inch. There are actually 3 variations of sashiko still commonly used: sashiko, hitomezashi and kogin. Hitomezashi requires only one stitch in any given direction with the end result being a design that is very dense and usually geometric in shape. If done well, it can actually resemble fine lace when finished. Kogin stitches are uneven in length and only follow the direction of the weft threads. The stitching instructions below apply to the basic sashiko variation.

The number of stitches per inch depends on the type of fabric, the number of layers, the type of thread used, and the ability of the stitcher. As a general rule, larger stitches are used for heavier fabrics and thread; smaller stitches for fine or lightweight fabrics and fine thread. For example, sewing with 3 strands of embroidery floss results in more stitches per inch than when using sashiko thread. IT IS IMPORTANT TO KEEP THE STITCHES AS EVEN IN LENGTH AND AS REGULAR AS POSSIBLE. Stitches of unequal length will be easily noticed in the design.

Use a needle that is comfortable and that can be threaded easily. Sashiko needles are best with the heavier threads, but embroidery needles or #7 or #8 sewing needles can be used also.

Generally, the beginning and ending thread is never knotted in sashiko. Instead, begin by taking 3-4 backstitches. Then stitch directly over the first few backstitches. Thread ends should be clipped as close to the fabric as possible. If a new thread needs to be started before the end of the design line, 3-4 stitches with the new thread should be layered over the old thread.

However, some people do use a method similar to that used in quilting for hand sewing on multiple layers. After the thread is knotted, the needle is inserted into the fabric at a distance from your first stitch (1/2″ to 3/4″ is a good choice for most people). If you’re using light coloured thread on a dark fabric, the needle should be inserted on the actual design line so that the thread does not show through. Pull the knot through the top layer and bury the knot in the sandwiched layers or batting. The needle should come up at the beginning of the design line.

Stitches can be ended using the traditional quilting method of backstitching over the last 3-4 stitches and then burying the end of the thread in the underlying layers before cutting.

Machine stitching on multiple layers requires a slightly different technique. When cutting your thread ends, leave enough length so that you can thread a hand needle in order to hide the thread ends between the layers. The ends of thread not finished in this way can often pull out over time, especially if the item will be receiving lots of wear and tear. The goal in both hand and machine stitching on multiple layers is to avoid having thread ends exposed whenever possible.

Straight lines are sewn without a break in order to avoid accidental curving of the line. Generally, multiple stitches are put on the needle before pulling the thread through. Advanced sewers may have as much as 3-4″ of fabric on the needle at any given time.

Curved lines are sewn by pulling the thread through after working only 2 or 3 stitches. If the material begins to pucker, hold the fabric firmly and gently stretch the fabric into position.

If the back of the stitched fabric will not be showing (i.e., if a backing cloth will be added later to cover the stitching), you can sew continuously with loops of thread on the back of the cloth connecting the beginning and end of two adjoining stitching lines. Do not leave too much slack in the loop–it should lay firmly against the back of the cloth. On multiple layers, the loops will be hidden inside the layers. If the back of the fabric will be showing, you will have to cut the thread at the beginning and end of each line of stitching.

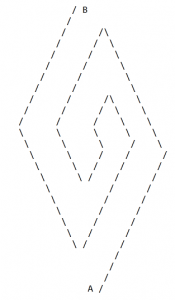

Sashiko is usually a “one-directional” stitching technique. A sample stitching pattern for the lightning (“inazuma”) pattern is shown below:

To stitch this design, you would begin at the bottom point marked “A” and stitch continuously until you reach point “B” at the top. This pattern would then be repeated over and over again in continuous columns or rows. Straight line patterns of this type adapt well to machine stitching because of the continuous sewing line.

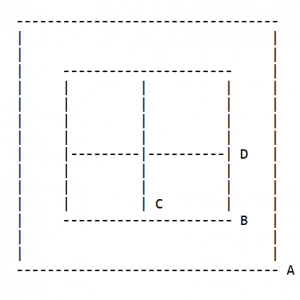

Depending on the pattern, more complex sashiko designs generally follow a set order of stitching: vertical and horizontal lines are done first, followed by diagonal lines, and then curved lines. Also, the individual pattern is usually worked from the outside to the inside. For instance, the “tsumeta” (rice fields) pattern below is worked by sewing the outside square first (beginning at “A” and going up), then the inner square (beginning at “B” and going up). The cross inside each inner square is done last (“C” going up from there, and then “D” going from right to left).

A repeat of tsumeta design means that the outer most square is stitched continuously across the entire row or coloum with the thread looped underneath between the repeats. Then the stitcher would work a pair of inner square and cross designs, cut the thread and then begin a new pair in the next repeat.

Obviously the choice of direction is up to the stitcher’s discretion. The starting and ending points given for the two designs above follow the conventional Japanese methods.

Pay particular attention to areas where threads intersect or turn corners. For sharp corners, the needle must either go into the point of the corner or come out from it. Corners must also be accurate right angles.

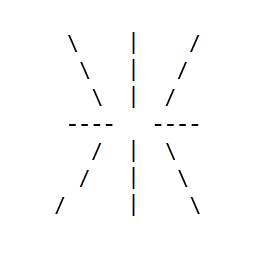

Intersecting lines will usually not meet in the center. Instead a small circular design is formed:

Altering Designs

—————-

Most common sashiko designs are made by combining squares, diagonals of squares, diamonds, hexagons or circles. As such, they can be readily altered by making the component parts wider or taller, or by drawing them obliquely to change the perspective. Sashiko patterns may also be combined to create more complicated patterns.

REFERENCES:

Adachi, Fumie. Japanese Design Motifs. New York: Dover, 1972.

Benjamin, Bonnie. Sashiko. Glendale: Needlearts International, 1986.

Matsunaga, Karen Kim. Japanese country quilting: Sashiko patterns and projects. New York: Kodansha International Ltd., 1990.

Mende, Kazuko ; Morishige, Reiko. Sashiko : Blue and white quilt art of Japan. New York: Kodansha International Ltd., 1991.

Rostocki, Janet K. Sashiko for machine sewing : Japanese-style quilting : classic to contemporary. Vandalia: Summa Design, 1988.

Saito, Rei. Sashiko Zukushi. Tokyo: Bunka Shuppankyoku, 1986.

Yang, Sunny and Narasin, Rochelle M. Textile art of Japan. New York: Kodansha International Ltd., 1989.

This is a compilation of QUILTNET postings about Sashiko. All comments are the OPINIONS of the person who posted the message…..

Featured image shows traditional kimono detail of kaki no hana (persimmon flower) design seen at the shoulders and hemline.

World Wide Quilting Page, USA

PROFILE

The World’s Oldest & Largest Quilting Site

A website by Sue Traudt.

Archived information at quilt.com